Bali - Fiction by Geronimo Tagatac

Bali - Fiction by Geronimo Tagatac

"Hunger was beginning to stain my whole morning. It smudged the sky and made the sidewalk seem harder under my dumpster joggers."

The cold woke me up on the floor of Frank’s studio apartment. My jacket had kept my upper body warm but my legs felt as though they’d spent the night in a pool of water. I remembered someone once telling me—maybe it was Frank—that you could burn to death in your bed without waking, but you’d never sleep through cold. Frank had shared his last half bag of potato chips with me and let me spend the night at his place. He’d lost his busboy’s job the week before and was looking for another restaurant job. He was always saying that when you work in a restaurant, you never go hungry. People left whole steaks uneaten. He was right, too, judging by the leftovers that he took out of the back door of Stuckey’s Restaurant at the end of his shift and shared with me.

I could tell by the light that filled the apartment’s two front windows that it was late in the morning. I slept a lot then. When I got up, I found that Frank was gone. I couldn’t remember hearing him leave. Maybe he’d found another busboy’s job. I went into the bathroom to wash my face. I looked into the mirror, at my dark, twenty-two-year-old face, and I saw lines around my mouth and eyes that hadn’t been there a few weeks before. I let myself out and went down the creaking, unlit stairs to the street. The February sun looked like a forty-watt bulb on the other side of a dirty gray sheet, and the wind chilled the right side of my face. My legs felt as stiff as stilts, but I was too hungry to stay put. I knew that I had to find a place where there were people with spare change.

I started walking down Ninth Street, toward the cluster of shops and cafes at San Carlos. As I walked, I kept my eyes on the sidewalk and the gutters, hoping to see the glitter of lost change, or maybe a stray dollar bill. I had found a five once and it made my whole day. I checked the change returns of all the public phones I came across. Nothing.

An old woman in a blue, wool coat came down the sidewalk with a dachshund on a leash. When she was within fifteen feet of me, I tried to catch her eye, but she turned her head refusing to look at me.

“Excuse me, Ma’am. Excuse me, but could you spare a quarter,” I said in as soft a voice as I could.

She kept her head turned, never slowing her pace. The little dog pointed its sharp muzzle at me, like a warning finger, giving me a nervous, beady look as it goose-stepped by, running interference for her.

The first one of the day is always the worst, I told myself.

I kept walking south on Ninth, looking for the right stranger. A bearded, dark-haired man in a sports coat and tie, came out of Uncle Al’s Deli. He carried a small sandwich bag in his right hand. I waited until I’d caught his eye. That’s very important, making eye contact.

“Excuse me, Sir. Could you spare a quarter for some food?”

He switched the bag to his left hand and reached into the pocket of his gray slacks with his right. “Sorry. Just used up the last of my change,” he said, shaking his head and walking off.

Hunger was beginning to stain my whole morning. It smudged the sky and made the sidewalk seem harder under my dumpster joggers. A block short of San Carlos, I got the attention of a blond, fortyish woman who’d just gotten out of a dark blue, late model car.

“Excuse me Ma’am, could you spare a quarter for some food?”

As she clutched her patent leather purse close to her side, I saw her whole face turn into flesh-colored iron. “Why the hell don’t you go back to Mexico or wherever you came from!” She turned and walked quickly away from me.

“Thank you for your generosity, and have a very nice day, Senora,” I shouted, as she disappeared through the door of a gift shop called Balinese Dreams.

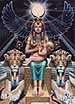

As I walked, I looked down at my feet, at the way they stretched out before me and pasted themselves to the concrete, pulling me down the block. I imagined that I was walking along a ten-thousand mile strip of sidewalk across the Pacific Ocean. Blue-green waves rose up on my left and right, between me and the rundown Victorian houses of San Jose. The sidewalk rose and fell with the rhythm of the swells. The wind grew warm and the air smelled of ocean.

Far, far ahead, where the edges of the sidewalk met and became a thin, black line, I saw a tiny patch of luminous green vegetation. I imagined nights where the moon rolled hugely through the soft air, and mornings were filled with bird cries and yellow, yellow light. The men and women would have dark eyes and brilliant smiles. Their children would stare at me and giggle. The old men would ask me to sit beside them, finger my strange, drab clothing, and ask me to tell them where I was come from. They would listen to me for hours. The women would be dressed in sarongs of brightly dyed cloth and they would stare, with frank curiosity, into my eyes. They would feed me and I would never again feel tired.

When I got there, I would send Frank a letter. I’d tell him to take Ninth Street south and keep walking.

Geronimo Tagatac is a first generation Phillipine-American. He spent his childhood living and working in the fields and orchards of rural California. He has published short fiction in the Writers Forum, Orion and Mississippi Mud. He can be reached by email at [email protected].